A common practice in political statistics models is to use the Bayesian model, which combines prior data (“the priors”) and current poll data to make inferences and predictions. Priors in the context of ORACLE are the results of past elections in a given state, specifically the two-party vote share that went to Democrats in an election. Blair Partisan Index (BPI) attempts to capture how Democratic a state would vote solely based on past elections, weighted by the values seen in the table below. The purpose of BPI is for our model to not rely too much on polling data, in order to offset potential polling error.

| Election | Weight |

|---|---|

| 2014 Senate | 0.05 |

| 2014 Governor | 0.04 |

| 2016 Presidential | 0.042 |

| 2016 House | 0.035 |

| 2016 Governor | 0.06 |

| 2018 House | 0.0435 |

| 2018 Senate | 0.1 |

| 2018 Governor | 0.1 |

| 2020 Presidential | 0.15 |

| 2020 House | 0.0945 |

| 2020 Senate | 0.11 |

| 2020 Governor | 0.1 |

BPI is then adjusted using national generic ballot polls (BIGMOOD), creating a new index called BABOON. We then use this prior data by combining it weighted with poll averages to get our final predicted Democratic vote share for a given election--in other words, the mean of the distribution that we will be pulling results from. (Note: for the governor’s races, BIGMOOD is not used in calculations and BABOON is set as equal to BPI by itself.)

The main benefit of using the Bayesian model is the balance between priors and polls. With states that have unpredictable priors and have had major political changes in recent years, the polls from the current race can stabilize the prediction. On the other hand, there are some races with a low number of polls and races with unreliable polling methodology. In these cases, the BPI can act as a reference of how legitimate polling data seems, and can provide some sort of prediction in the case of very few polls. Additionally, BPI will fail to capture rapid political shifts such as In states like Georgia. This is because our calculations of BPI consider past elections from 2014-2020. However, as political leanings change in a certain state, past elections may not accurately reflect the current political climate.

Methodology

There is a point in the modeling process where poll percentage values and BABOON are combined by a weighted averaging, with weights being determined by the number of polls for a given election. To get rid of priors for this thought experiment, we set the weight of BABOON to 0 in this averaging, instead of using an exponential function to determine weights. This means that our final percentage of two-party votes for Democrats and the mean of our distributions are only taking into account polls.

Results

To show state-by-state differences between the base ORACLE results and the results of not using BABOON in our calculations, we made maps of percentage of predicted vote based on data from October 18th, 2022.

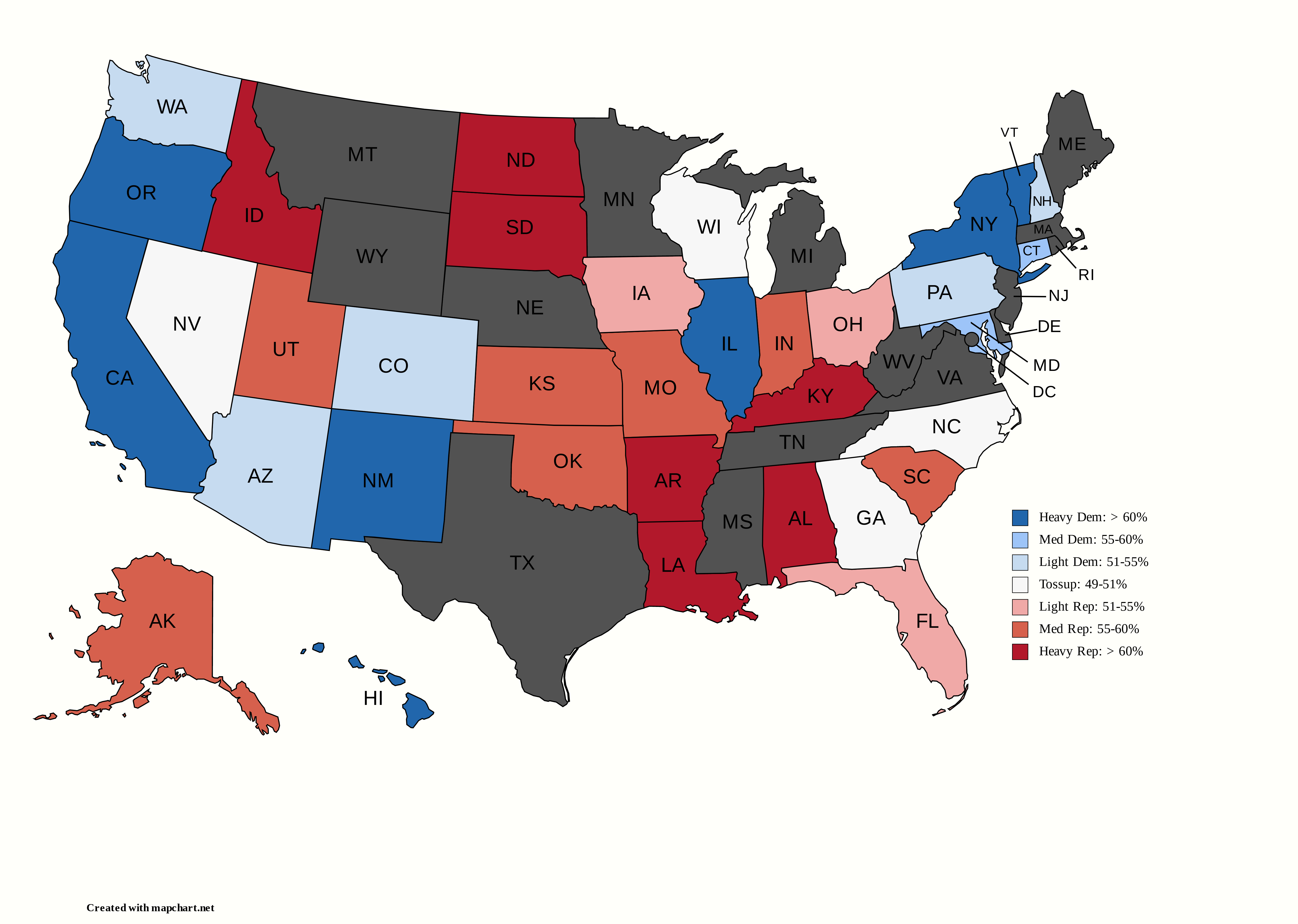

Senate Map from ORACLE

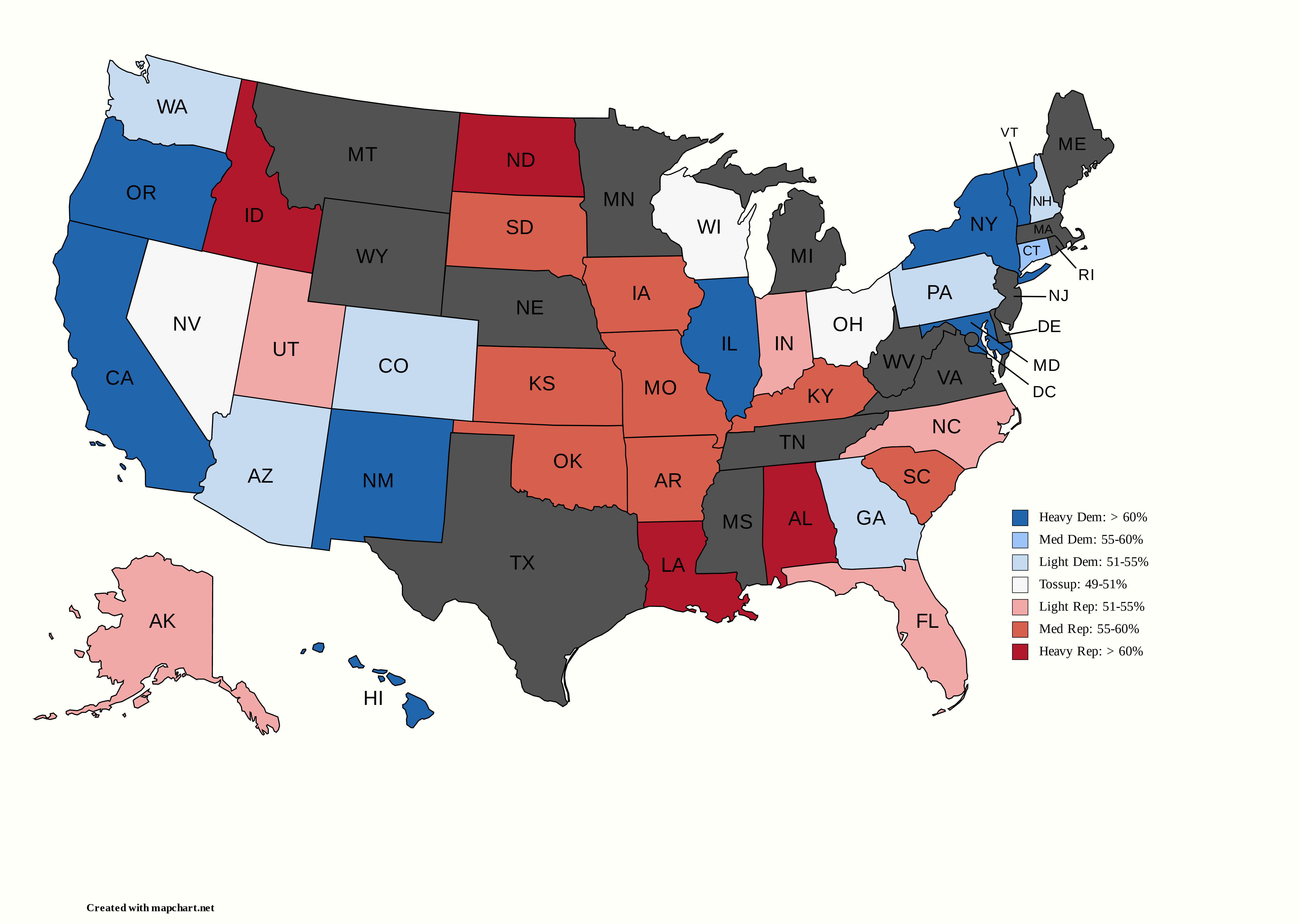

Senate Map with no BABOON

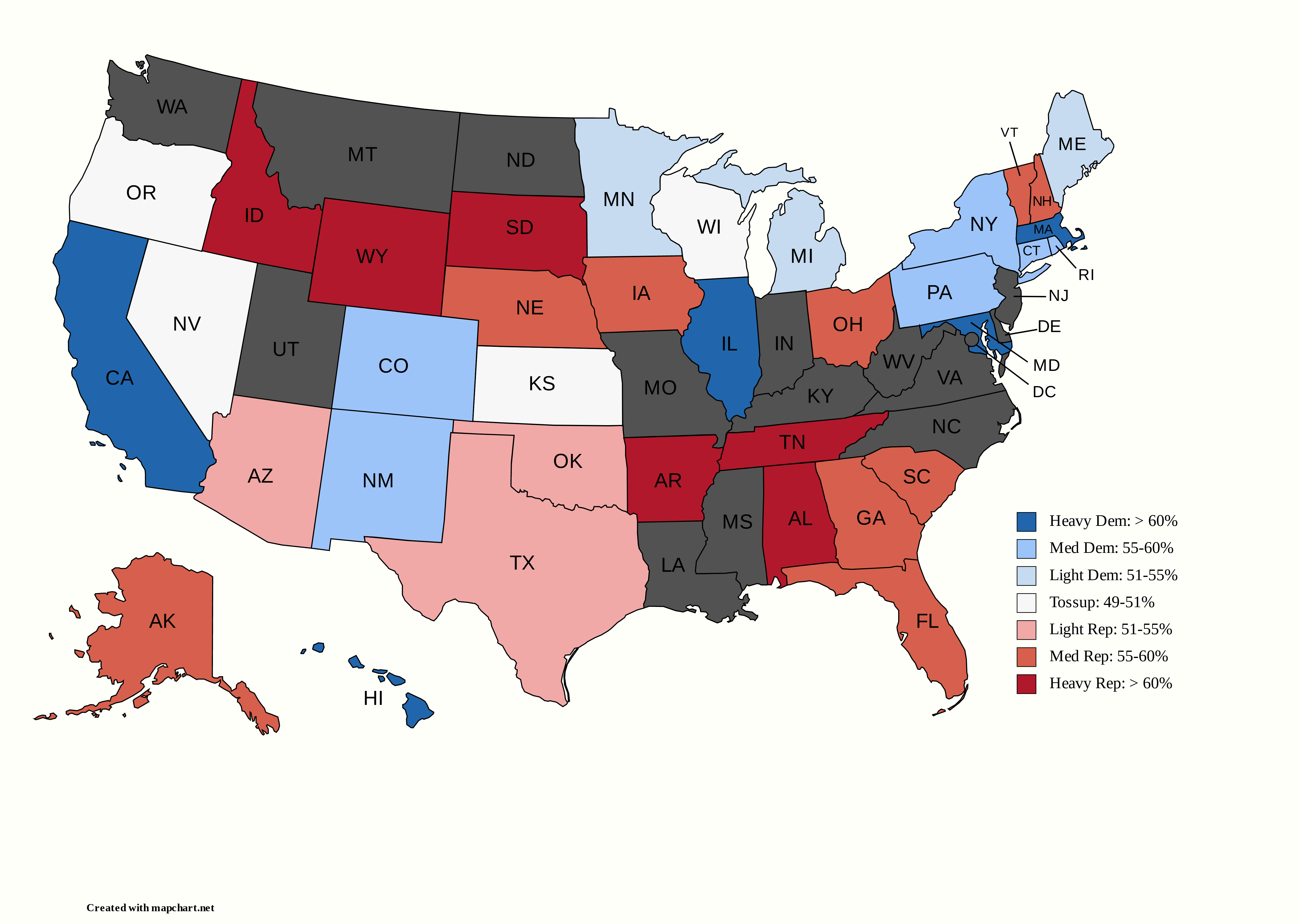

Governor's Map from ORACLE

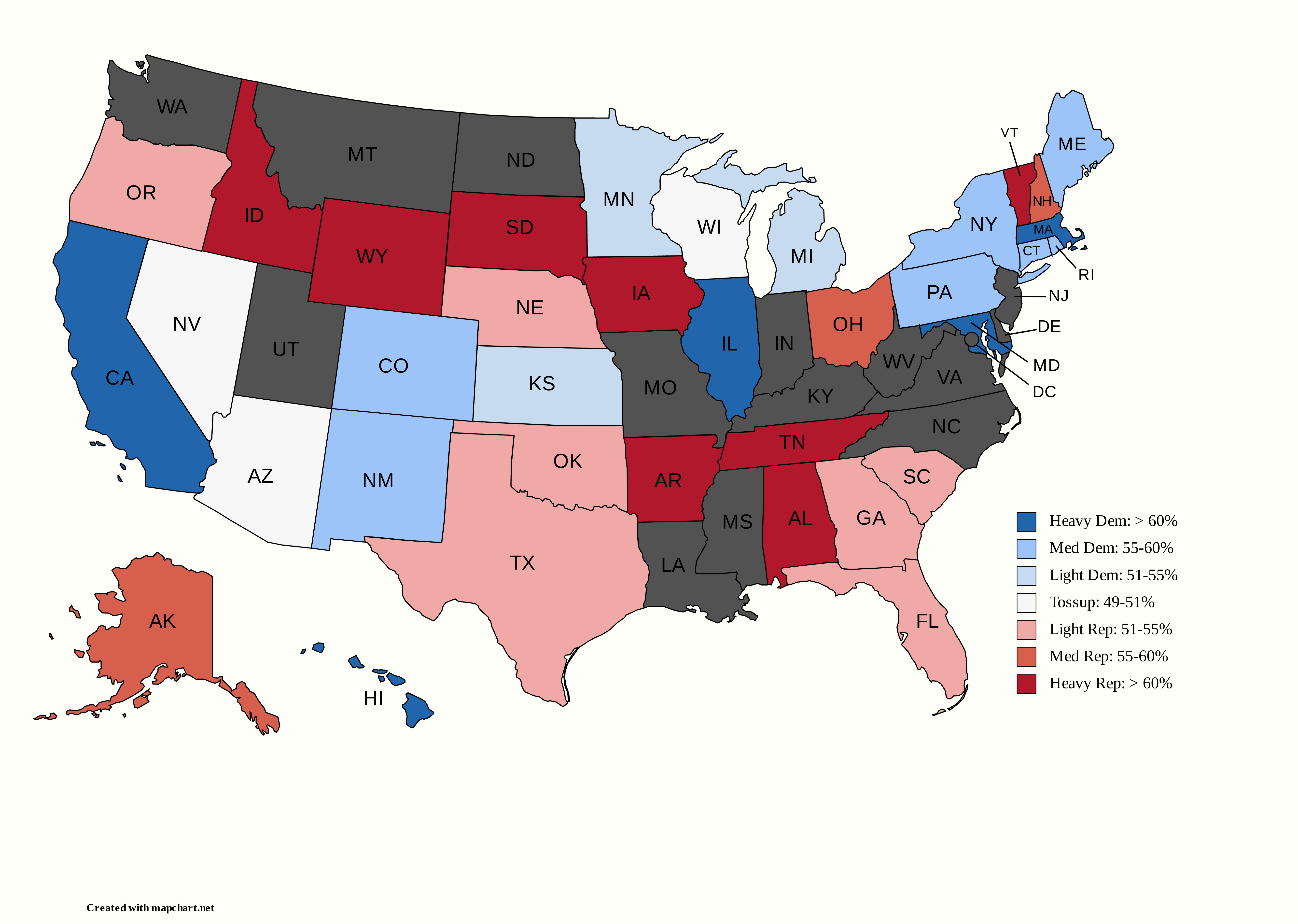

Governor's Map with no BPI

Along with these mappings, we did match-paired T-tests to see if getting rid of BABOON had a statistically significant effect overall. In basic terms, this test assumes that there is no difference whether we are using BABOON or not and then quantifies how likely achieving the actual results is under this assumption. The numbers that describe this are called p-values. For both the comparisons for the Senate and the Governor races, our tests revealed very high P-values, of 56.8% and 48.6%, respectively. Essentially this is saying that if we assumed there was no difference, we would see results like the ones we got about half of the time. This means that there is no evidence of a difference between models with and without BABOON.

Analysis

Overall, most of the changes we saw were in red states. Most states generally shifted to lean slightly less towards Republicans. However, with our methodology, we saw a more significant effect on previously Republican-leaning states than previously Democratic-leaning states.

Within states with contentious elections, there were a few notable changes after removing BPI/BABOON. With Senate races, the most notable changes were with Ohio, Georgia and North Carolina. Ohio and Georgia became more Democratic, with Ohio becoming a tossup election and Georgia going from a tossup to Democrat-leaning.

On the other hand, North Carolina went from a tossup election to Republican-leaning, which was also one of the few instances where states became more red. According to the ORACLE page for North Carolina, the BPI (49.57%) was higher than the polling average (48.65%). The difference between these two values was just enough to cross our threshold for what a tossup is (49%-51%). Furthermore, in the 2016 Senate race, the Republican candidate won with 52% of the vote. By removing the BPI, the main value in consideration was this previous election, which caused the state to go from being a tossup to slightly Republican-leaning.

| Senate Race | ORACLE Democrat % | No BABOON Democrat % |

|---|---|---|

| Ohio | 48.974% | 49.430% |

| Georgia | 50.996% | 51.763% |

| North Carolina | 49.047% | 48.992% |

Gubernatorial races followed similar trends as Senate races: after removing BPI, the previously red states became less red, while the previously blue states did not have many changes. The only exceptions to this trend were Oregon and Kansas. Oregon went from a tossup to Republican-leaning, and Kansas went from a tossup to Democrat-leaning. Kansas’s change was likely because there was only one poll within the last month that we were using. Despite Oregon’s past Democratic voting history, the Republican candidate was polling higher than expected. Since we are relying on polls only, this race is one in which BPI would have a strong effect.

| Governor's Race | ORACLE Democrat % | No BPI Democrat % |

|---|---|---|

| Oregon | 49.569% | 47.463% |

| Kansas | 49.700% | 52.875% |

Conclusion

We did not find a significant change between election results with and without BABOON. However, not having it forces us to rely on polls completely. If there are lots of polling errors, then we have no cushion to account for that. Furthermore, in polls with only a few polls, relying too much on the priors leads to more fluctuation and unpredictability. There is no right way to do political modeling, but it is important to consider different strategies like using priors or not using them.